The 18th of October, the title of an editorial of The Japan Times kept my attention: “A more user-friendly legal system.” Since the task of this report was recently assigned, I followed the content critically. The theme of the article was a new support center for citizens with legal problems, intended to close people to the justice administration. In few words, a subsidy for the use of legal services. I found this fact very surprising and at the time illuminating to guide this report. Why should Japan make such effort? I was pretty sure that all kind of the disputes that are subject to legal intervention – from a Western logic – take place in everyday Japan, so what do people rely on to solve this problems if not laws? The following are just the initial findings from a restricted bibliographical review about the topic, in which the intention was to find, out of some issues of common life, the role of laws and norms.

Brief definition

Mr. Mark D. West, in a revision about how decision making in the world of Japanese Sumo, presents a conceptualization for the terms law and norm in order to accomplish his study case. First, Law “refers to legislative and judicial provisions as well as the organizational rules […]” the latter referring specifically to those approved by a governmental institution, such a ministry. On the other hand, norms are constrains that come directly from the society, which regulate many transactions in the real life but are not enforceable by legal means.

To illustrate the concept of norm, herby reproduce a classification of them presented by Ellickson, cited by West:

“Ellickson categorizes each rule and norm as one of five types: substantive (rules or norms that ‘define what primary conduct … is to be punished, rewarded, or left alone’), remedial (provisions that dictate ‘the nature and magnitude of the sanction to be administrated’), procedural (provisions that ‘govern how controllers are to obtain and weigh information’), constitutive (provisions that ‘govern the internal structure of controllers’), or controller-selecting (provisions that govern the ‘division of social-control labor among the various controlers’).”

The connotations of these definitions in the world of Sumo would be addressed at the end of the report.

Historical Hints

When adopting an historic point of view, it is easy to follow the origins of the present Japanese legal system. During the Meiji Restoration, in the process in which Japan finally opened its doors to the rest of the world, it was a priority to catch up with the Western societies. Regarding the legal system, it meant the government to quickly adopt German and French codes to rule the territory. However, nothing was made about morality and customs of Japanese people, neither the regulations adjusted to their reality. In fact, aware of the incompatibility between the Western values around democracy and the monarchical model adopted, the Meiji leaders restricted the introduction of the former ideas and elaborated kokutai – an explanation of Japanese about what is Japanese.

It has to be taken into account that also the Japanese constitution, established after the defeat in the Second World War, was an imposition of the United States, instead of a reflex of citizens’ claim for structural changes in the government.

Evidence of the existence of this duality of codes could be followed – along with an open criticism – through the essay “Darakuron” (“On Decadence”) by Sakaguchi Ango, in 1946. In it, the author openly recognizes the division when he states:

“It has been said that one reason the Tokugawa Shogunate made the decision to refuse a pardon to the forty-seven loyal retainers and uphold the punishment condemning them to commit ritual suicide was due to a feeling of paternal sympathy, for if the retainers had lived out their lives to old age they would have suffered the shame of public display and someone would surely have appeared to tarnish their names. Such human feeling does not exist in today's laws. But it does remain to a large extent in the people.”

Beyond the duality, the author give clues of a long tradition on this class of rules or norms, at the time he starts an argumentation of its consequences, focusing on codes as the Bushido and the figure of the emperor.

Linking to go into detail, two quotations from a research made in 1953 - when the studies were somehow more related to understand why Japan went to the war – detect the two sets of rules and also introduce us to the explanation of the situation. The first, Kerlinger citing Reischauer about norms, finding “… ‘a far more rigid adherence to a detailed set of social values’ than we know in west.” And then, from interviews about educating children in their first stages of life: “One parent in Takashima said that she never forced the child to sit properly, but that when children get to about three, they understand how things are done.” Like everyone, no?

Two worlds

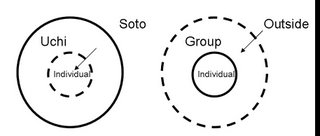

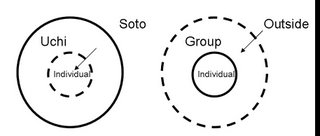

Fostering the reasons of the low crime rate in Japan, compared with other developed countries, Komiya presents a very comprehensive explanation of the cultural roots of the situation. The duality enounced above came to fit perfectly the Japanese perception of their social environment. This is one divided between the people who belong to their group – uchi (内 or 家?), which includes the people in the home, the company, the university, etc. – and the outsiders – yoso. Consequently, when dealing with individuals belonging to the latter, it is expected to make use of the law, while for the “house” the giri – Japanese traditional duty – should be enough to solve any kind of inconvenient.

The giri that rules the inner world, far from a fixed code, is a kind of obedience and dependence bond to the superiors, different to every specific case, tied to the characteristics of the linkage, “particularistic, personalistic and relativistic”. Examples or the way it works are:

- When two parts sign a contract, they are expected to become members of a same uchi, so they hesitate to ask about the written details, because could be offensive to the relationship.

- Japanese do give small, if any, gifts to their relatives, while they give ostentatious presents to their bosses twice a year.

Figure 1. Comparison of Individual consciousness between Japan and the West

Source: Komiya, 1999. Pg. 376

The benefit from abiding the giri is a paternalistic support of the bosses and, as a result of the sum of the whole uchi’s giri, the comfort of being able to rely on the group while one is doing its job. Nevertheless, as this reward is subjective to the discretion of the superior, disagree and tension may arise when someone is not satisfied with his part. In these cases, any confrontation is avoided because it would menace the harmony of the uchi, thus it is resolved by mutual understanding or the intervention of a third part, which must be also part of the uchi.

The uchi relationship has an important peculiarity: it strongly depends on the territory. The links between the members of an uchi resembles more a neighborhood than an academic community. Hence, the action of giri is also one that aims to homogenize the big disparity between the backgrounds and attributes of the members, instead of motivate talents. To do so, rules of conduct plus emotional commitment are equally addressed. Besides, out of the complexity of managing the diversity of the group, the amount and detail of norms that govern the conduct inside a given uchi tends to be enormous. These norms include features on decorum, morality and civility, such as “modes of speech, dress codes, bowing manners, and even styles of walking.”

From the territoriality and the giri, it is clear that the uchi has a characteristic vertical structure, commanded by seniors instead of the particular merits of the members. Therefore, in this organization it is important to: rank the members for their contact to the group (time) instead of their capabilities (merits); then, place little weight in the difference among comrades; and have a common objective around which all of them fight, relying in the complex set of rules to satisfy disparities.

To sustain this kind of social structure, it is essential to maintain a strict control over the members of the group, so the rules are not forgotten or transgressed; but as the uchi is ruled by such a complex network of norms, it should be introduced by long training periods in the companies, morning assemblies, communal night drinks and pleasure trips. People who are not obedient to the rules is acknowledged and reconvened. If the behavior continues, they would be excluded. So normal Japanese are tight to a constant conform of social norms and respect to the seniors, making them to look for the existent rules – or to imitate the reaction of a superior - when a new situation comes, before acting by universal principles.

By contrast, the yoso world could be seen like a wild place where it is not possible to rely on the trust of anybody. Then, the legal codes come into action, although with a small change: given the duality stated above, laws recognized as external, either are used as corresponding to an egoistic effort to prevail, disregarded as inexistent, or scorned as obstacles to the natural behavior. Examples of those attitudes could be, in order: sues about impact of pollution on citizen’s health, the short concern between population (with very important exceptions) about human rights, and the great amount of bicycles parked around the downtown of Sendai – where it is clearly prohibited to do so.

Additional outcomes of this social structure – worth to be at least enounced here – are: the difficulty to belong to two or more groups at the same time; the high value placed on people self-control, required to manage the amount of codes; and also the high level of elaboration on details beyond the norms – in the uchi or any permitted hobby – as it is the space to develop their individuality.

The Thread in different Nets

Although just one part of the big range of causes a real-life problem can have, looking to the peculiar glass of the Japanese culture of groups and the giri could be crucial to understand the state of affairs on every issue which involves social participation in the country. Hence, according to findings and my interests, I present here some issues from the literature with comments over the presented perspective.

Crime rate in Japan

Accepted the above framework, the author points two more facts related to his objective: the Japanese type of group is much more inclusive than the Western, because of their territoriality and the homogenization of their members abilities; and the subjection and appreciation of members of the group through their conform to the complex set of norms, what makes them more aware of not misconduct in anyway during their daily life.

However, there are Japanese criminals, which the author groups in four categories:

- Individuals who do not care about the uchi, do not understand it, or do not develop enough self-control.

- Criminal norms respected from the head of the uchi.

- Crimes without victims cannot be controlled.

- Those exiled or who fled from the uchi.

Tobacco and Alcohol Control

Although these two issues are relatively different in their economical background, their common roots in cultural practices and the relative failure in their control could be a clear link between their realities. From everyday life in Japan, the high level of consume of alcohol and tobacco is evident. Furthermore, this practices fall into the group activities to tight contact. In few words, relating to the scope of this work, the two articles reviewed in the issues show that no deep legal measures have been developed to counteract their impacts on society, even though scientific data is plentiful. Most of the actions are related to reports by the ministry and voluntary regulations adopted by the companies. No special political support was given to the citizens groups, while economic measures were somehow weak – with the exception of beer and whiskey for its special characteristics. In the chase of tobacco, political will its being changing with a lag of 30 years, on which courts have generally rule in favor of the companies. The mass media role seems to be limited to make public the facts, but with no role on social control.

These facts leave questions on assumed images from Japanese people: their awareness around health and their trust on science. Also it would be interesting to make further research on the characteristics of Japanese democracy.

Sumo

The author focuses into demonstrate how the presented social structure and set of rules is closely related to the behavior of a company. In this sense, the norms assure economical control in the organization, best allocation of resources and reduction on transaction costs- or avoidance of tasks that would require big effort for resolution, as the eligibility of elders and directors in the association. Extrapolating, these advantages from the normative structure should have relevance in explaining Japan’s economic miracle, issue not reviewed.

Other comments

Komiya, at the end of his article, points out that the normative model of Japan and the West differ in the punishment expected to the offenders, being it deprivation of membership to the members of the former, while stigmatization for the latter. But, bringing the considerations around AIDS that guided the seminar this semester, it would be interesting to analyze how a stigma would alter groups not used to manage that kind of exclusion. For example, some success in western countries to counteract alcoholism and tobacco consumption has been stigmatization of those groups. Could this have relation with their failure? Could it help to reorient or understand public health measures adjusted for Japan? I hope not being so naïve making these assertions – or at least be on time to wake up.